e-mail reminder

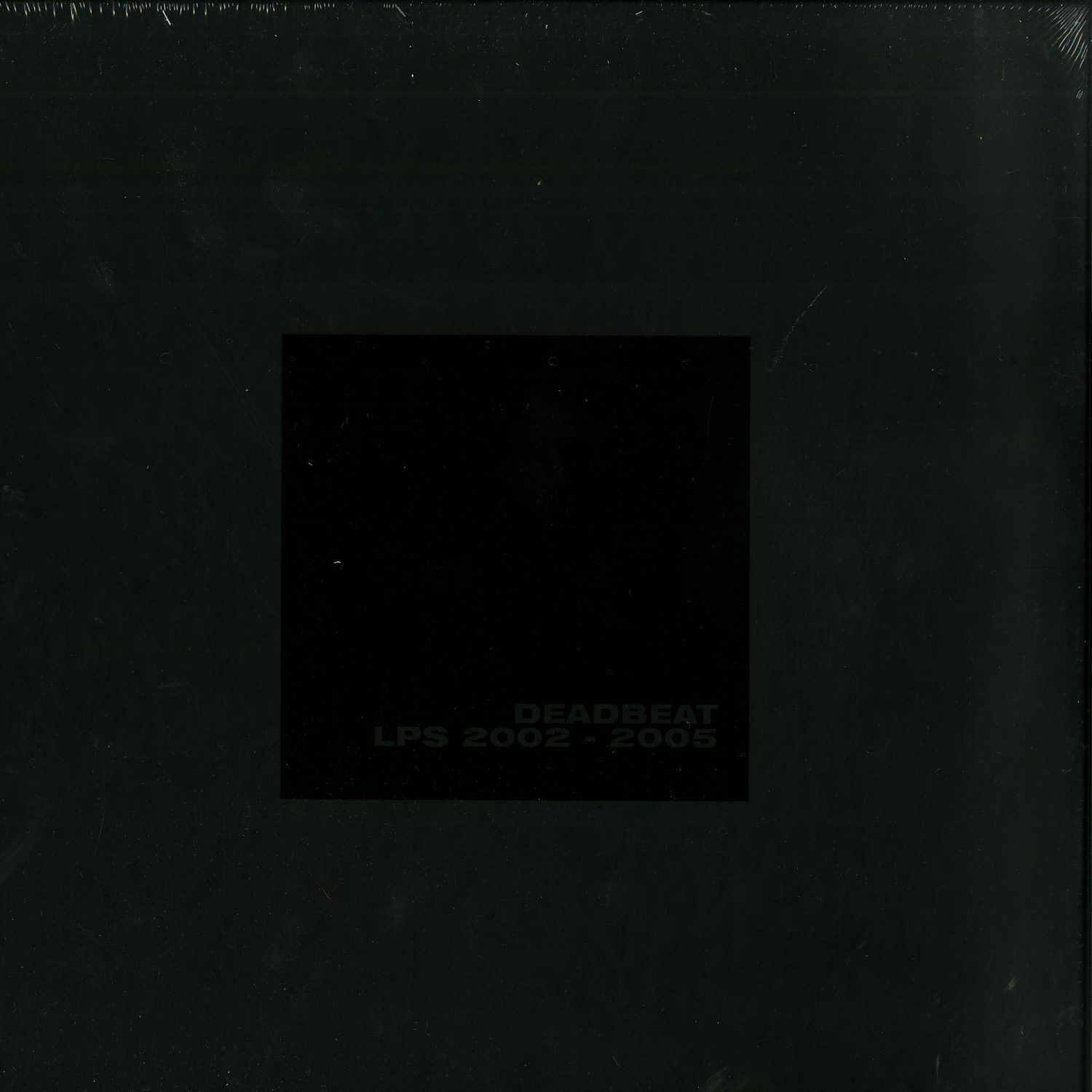

If this item in stock, then you will get an infomation E-Mail!Limited Edition (500 Copies Ww) 6xlp Box Set With Remastered Versions Of Deadbeats Early LPs.

Sales Information:

Ever since launching his production career at the turn of the century, dub-techno auteur Scott Monteith has been nothing if not deeply prolific. The Canadian-born, Berlin-based producer's nine Deadbeat albums and nearly two-dozen singles represent one of most prolific and consistently rewarding catalogues in 21st century electronic-music canon. It's a spectacular run of records that continues to hit new heights, as witnessed with the widespread acclaim that met his most recent album with Paul St. Hilaire, The Infinity Dub Sessions. Continuing the reissue campaign of his early output that began with 2001's Primordia last year, Monteith's BLKRTZ imprint is now set to release a massive 6-vinyl box set of his most iconic Montreal albums: 2002's Wild Life Documentaries, 2004's Something Borrowed, Something Blue, and 2005's New World Observer.

2002-2005: The Montreal Albums

Taken together, these three Montreal albums capture the Deadbeat project at its most contemplative and intimate, as far from the club speakers as it would ever get and tuned inward instead. Released a year after moving to Montreal, the roots-reggae revisionisms of Wild Life Documentaries proved to Monteith's international calling card. This sophomore Deadbeat album was the first to see release on Stefan Betke's (aka Pole) ~scape imprint, which in 2002 was considered the premier venue for dub-directed electronic music in the world. The album pitted the Montreal producer alongside contemporaries such as Jan Jelinek and Kit Clayton. Two years later, Monteith returned with Something Borrowed, Something Blue, the most introspective album of the entire Deadbeat catalogue, and also the album from this early period to attain the most critical acclaim. With the international success of these two ~scape albums under his belt Deadbeat and Jan Jelinek proved to be the label's biggest sellers Monteith quickly turned the corner and released the bristling, politically charged New World Observer album in 2005. A year later, the producer would make the move to Berlin, joining a generation of Canadian producers who'd launched careers at to become frustrated with the limited growth potentials of the North American market at the time.

Certainly the city of Montreal played an outsized role in the sonic depths of these recordings. "I worked a desk job for a music software company, but would come home every evening and quite literally lose my self in sound until late into the night," he remembers of this period in his life. "When I eventually left the company in 2003, this became a full time affair and I often didn't even bother to get out of my pyjamas for days at a time. My good friend Robert Henke recently said, in an interview, that the only thing an artist truly needs to create is the space and time to do so. By that measure, this period in my life was a golden age, providing glorious amounts of both. My studio at the time was very meagre, a little grey room with a half-rotten balcony, some not very good speakers, even worse computer and a not very comfortable chair. It was my first full-time studio though, and I made things in that little room each and every day that made my heart race and left my mind reeling at the seemingly endless possibilities the simple act of making sounds and music opens up."

Outside his tiny studio, Monteith was surrounded by a community of electronic musicians who were in the midst of putting Montreal on the international techno circuit. The producer lived above Marc Leclair (aka Akufen), whose Perlon EP "Quebec Nightclub" and 2002 Force Inc. album, My Way, would become an instant classics of the burgeoning micro-house sound that was synonymous with the city. The cut n' paste technique can be heard bubbling up most clearly in passages of New World Observer, which followed Monteith's fruitful collaboration with micro-house producer Stephen Beaupré as the duo Crackhaus. Fellow Kitchener-native Mike Shannon had also moved to the Quebec metropolis and was responsible for releasing several of Monteith's early EPs via his labels Cynosure and Revolver. Ambient powerhouse Tim Hecker also got his start in the Montreal of those years, and was never too far from this tightly knit web of like-minded producers. Creativity and, more importantly, productivity, were in the air, and those underpinnings helped set the tone

Deadbeat, Dub, and Techno

Few producers have bent the dub-techno template to suit the demands of the moment as successfully as Scott Monteith. And whereas his most recent BLKRTZ albums have been defined by Berlin's ever-morphing club culture, these long out-of-print early albums that first elevated the Deadbeat moniker to international recognition are reflective of another time, another place, and ultimately another context than the one familiar to a new generation of electronic-music listeners. Listening back to these three albums in hindsight, almost a decade after New World Observer's release, also begs for a re-evaluation of their original cultural context.

It's nearly impossible to overestimate the long shadow cast by dub-techno's originators over the work of the second-wave generation of producers who began using the template in the first years of the 21st century. For North American producers such as Deadbeat and Detroit's DeepChord, the challenge of overcoming that set of preconceptions proved even more difficult. They were, after all, taking on a form that was being created, consumed and thus evaluated by largely European audiences. In the miscast blanket of critical thought, they would be forever indebted to the pioneering work of the Chain Reaction/Burila Mix/Basic Channel families to one side and Stefan Betke's Pole recordings to the other. This context was further cemented by the fact that Monteith's introduction to the larger electronic community came via releases on Betke's ~scape label.

But shorn of that originating context all these years later, Deadbeat's Montreal albums reveal a different picture. There's a degree of depth and texture to these recordings that simply bypasses any notion of minimalism that was all the rage in discussions of the meeting ground between Kingston's dub low-ends and Berlin's fin-de-siècle avant-garde electronics. Looping repetitions swirling out ad infinitum are simply not part of the Deadbeat aesthetic at this juncture. Instead, the listener finds an inordinate amount of attention being placed on narrative and musical storytelling. The low-end mindset definitively draws from dub and the technology employed is part and parcel with techno but, beyond that, these albums are also deeply melodic affairs that borrow from a wide-ranging palate of musical ingredients.

These albums are dubby, yes, and not quite techno at all. There are refractions of Krush, Vibert, and Vadim-like trip-hop pacing at work here a deeply unfashionable position to take back in the early-2000's but an era of music that's gaining traction once again now. There's the moodiness and syncopation of Warp-era IDM at work here too. Micro-house collage techniques emerge in the sampling. All of this is to say that, in hindsight, the Deadbeat at work on these three albums is a synthesist, not a purist. His vision of dub-techno was less keen on sonic formula and more open to narrative concept than the standards set by the pioneering dub-techno of the mid- to late-90s. Removed from the timeline that defined them within the footsteps of dub techno, listeners shouldn't be surprised if they hear something altogether different at work here.

Dmitri Nasrallah

GTIN:

880319684838

code:

c46-99

VÖ:

10.11.2014

backordered:

08.05.2019

Customers who bought this item also bought :

more releases on label

more releases by artist

* All prices are including 0% VAT excl. shipping costs.