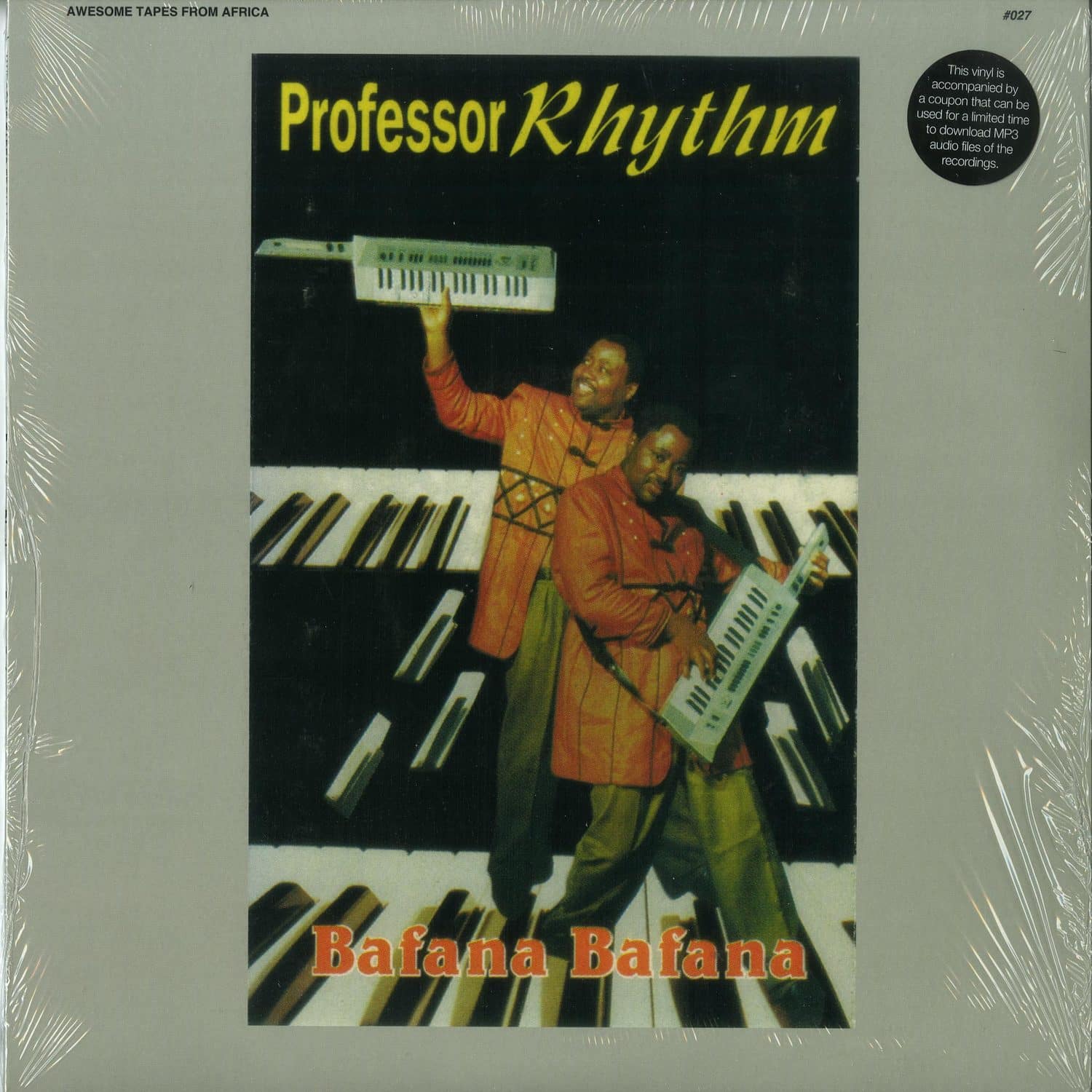

BAFANA BAFANA

Professor Rhythm is the production moniker of South African music man Thami Mdluli. Throughout the 1980s, Mdluli was member of chart-topping groups Taboo and CJB, playing bubblegum pop to stadiums. Mdluli became an in-demand producer for influential artists (like Sox and Sensations, among many others) and in-house producer for important record companies like Eric Frisch and Tusk. During the early 80s, Mdluli projects usually featured an instrumental dance track. These hot instrumentals became rather popular. Fans demanded to hear more of these backing tracks without vocals, he says, so Mdluli began to make solo instrumental albums in 1985 as Professor Rhythm. He got the name before the recordings began, from fans, and positive momentum from audiences and other musicians drove him to invest himself in a full-on solo project. It was the era just before the end of apartheid and house music hadnt taken over yet. There wasnt instrumental electronic music yet in South Africa. As the 80s came to a close, that was about to change.

Professor Rhythm productions mirror the evolution of dance music in South Africa. They grew out of the bubblegum moldwhich itself stems from bands channeling influences like Kool & the Gang and the Commodoresinto something based on music for the club. His early instrumental recordings First Time Around and Professor 3 mostly distilled R&B, mbaqanga and bubblegum grooves into vocal-less pieces for the dance floor. Musically, these were a success and commercially the albums all went gold. There were countless bubblegum albums flooding the marketplace, with nearly disposable vocalists backed by mostly similar-sounding rhythm tracks. Most of the lyrical content was light and apolitical. But the keyboards used formed the musical basis for what would come next.

Kwaito can refer to many things. Musically speaking, it runs the sonic spectrum from slow house music with chanted raps and repeated phrasesbuzzy slang and/or woke messagesto faster beats-per-minute, four-on-the-floor house music with deep, soulful, sung vocal flavor. Mdluli simply describes kwaito as, like club music with a township style. The townships, segregated suburbs where blacks were forced to live, on the outskirts of Johannesburg and other cities, were where kwaito evolved into a distinctly South African form of dance music and hip-hop.

As democracy emerged in South Africa, so too did free expression. Music didnt get censored any more and black citizens became more vocal in discussing the stark racial and economic imbalances. At the same time House music records from Chicago and New York had filtered into South African consciousness, and by 1994 there were DJs and club nights and record stores spreading. Blacks could move freely and own businesses. The connection with and availability of music from overseas had never been stronger.

By the time Professor 4 and this recording Bafana Bafanathe name references South Africas national soccer teamwere released in the mid-1990s, kwaito had fully emerged. Access to instruments and freedom of expression helped its rise in influence among youth. According to Mdluli, Once Mandela was released from prison and people felt more free to express themselves and move around town, kwaito was becoming the thing. Lyrically, kwaito championed the local township lingo while adapting international music, house music, into the local context. International Music, as house music and early kwaito were interchangeably known, in many ways reflects the sounds coming from America. But South Africans made it their own. Today, the largest part of the music industry is occupied by house music and its relatives.

To Mdluli, house music means music made at home. During apartheid, private recording studios, or home studios, didn't really exist. They recorded at the studios of companies like Gallo, EMI and Warner Brothers. Furthermore, Mdluli points out the crucial importance of engineers, who played a role from start to finish in the studio with most artists making kwaito in the early days. Blacks were not allowed to study sound engineering in school, Mdluli explains. So they often didnt have a working background in the studio arts in those early days. But once more people gained access to home studio equipment, the earliest kwaito recordings flooded out from the urban centers, especially Pretoria and Johannesburg.

Availability of synths, sequencers, computers and drum machines grew and the tools used to create pop music in major studios were democratized to the point where many home studios proliferated. Some early kwaito producers would stay home to guard their hard-won studio equipment. Because of his earlier success, Mdluli didnt work in a home studio for this recording and avoided the mixing problems heard in some early kwaito home studio cassettes. With the extensive help of studio engineer Nick Heaton, Bafana Banana was recorded using a Roland MC-500 sequencer and Yamaha DX7, Juno 60 and Korg M1 keyboards.

More recently, Mdluli slowed down making Professor Rhythm tracks, as demand for his production work with other artists increased steadily. His work with gospel group IPCC has led to million-selling award-winning releases. Mdluli runs his own music publishing company along with his Studio 12 recording studio. His many successful projects run the gamut of South Africa's rainbow of musical styles. He does well focusing on genres that still sell amid South Africas challenging piracy landscape, including mbaqanga, Shangaan music, jazz, Zulu traditional, maskandi, afrosoul and more.

Mdluli makes clear that as the popularity of English-language bubblegum pop shifted to kwaito during the period of Mandelas release from prison and the dismantling of apartheid. The country was in turmoil, there was violence and crime in the streets. The upbeat music he made as Professor Rhythm sounds the way it sounds, because people would make themselves happy with the songs we were playing then. When they listened, it took them to different places than they were at the time. [info from label]